The Texas Imaginary

The center of Fort Worth is dense with connections to the American West, but travel a little ways north and that all gives way to the placeless suburbs and more directly Evangelical words and codes.

My parents weren’t from Fort Worth or even Texas. I hadn’t grown up here. They moved to Texas from Southern California when they retired, taking advantage of the low cost for housing. My Dad had died some years earlier, and now as the death of my Mom approached I began examining the layers of meaning and faith supplied by Fort Worth, their final, chosen home.

Fort Worth served as a gathering point for the Chisholm Trail, the place to which cattle were driven from further south in Texas. The cattle were then driven in great herds north to Abilene, Kansas. In the two decades following the Civil War this cattle drive along the Chisholm Trail delivered over 5 million head of cattle to markets. This is all treated as a Western story, but we should connect the dots: the cattle were driven north to reach the railways, which delivered them to the stockyards of Chicago. From Chicago the meat was transported in refrigerated rail cars to the East. It’s an American story we isolate and label as “Western.”

While my Mom was in the healthcare facility that would shortly turn into hospice, my wife and I took an evening to walk around downtown Fort Worth. We found comfort in the declining temperature of the evening, and in the easygoing downtown that took our mind off the bleak forecast for my Mom’s life. That mural celebrating the Chisholm Trail marked the center of Sundance Square. It was named after the legend of the West known as the Sundance Kid who robbed trains with Butch Cassidy but never came to Texas. I appreciated that Fort Worth was building a vibrant downtown, and it might well need to borrow a few names to construct an identity.

Amon Carter founded the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth. It was Carter who branded Fort Worth as the city “Where the West begins.” In geographical terms that’s a tough claim, but he meant something more like the home of the “Spirit of the West.” That gives a sense of how to view the above painting "Buffalo Runners—Big Horn Basin" (1909) by Frederic Remington. The painting hangs in the Sid Richardson Museum (a downtown Fort Worth museum founded by yet another Texas businessman turned collector of Western art). The scene depicted in the painting has nothing to do with Fort Worth since Big Horn is in Wyoming. But for Amon Carter or Sid Richardson this painting expresses a striving spirit that represented Texas.

The old Chisholm Trail and its long distance cattle runs existed for less than 20 years (1867-1884). Railroads were at that time connecting cities throughout the West, and the arrival of the Texas and Pacific Railway to Fort Worth in 1875 was the beginning of the end for long distance cattle runs. Fort Worth went on to become a wholesale market for cattle, centered on the Fort Worth Stockyards. The remains of these stockyards have become a popular tourist site. Every day at 11:30am and 4pm visitors line up to watch a line of Texas longhorn cattle get driven in a line down the main street, cameras and iPhones ready. This faux cattle drive began only in 1999 but its popularity reflects its combination of cowboys, the old cattle drives, and the later stockyards into a single repeatable event.

“John Wayne An American Experience” is a celebrity museum near the Fort Worth Stockyards. Yet you search in vain for anything connected to Texas in the life of John Wayne. He was born in Iowa in 1907 and then in 1916 his family moved to California. Somehow Fort Worth still scored this 10k square foot museum with original outfits, photos, and his 1970 Oscar for Best Actor. His only association to Fort Worth were the roles in Western movies, including the lead in Red River (1948), which portrayed life on the Chisholm Trail. But it’s not about one or two roles. Fort Worth wants to claim the mythic, individual West, and John Wayne could be seen as embodying that idea.

Fort Worth successfully conveys its civic fantasy in its downtown and Stockyards. But the city doesn’t end with that center; it extends north along Interstate 35W. Fort Worth has about doubled in population since the year 2000, and most of that growth has been absorbed by the sprawl of the northern suburbs. This was the area where my parents had bought a house. Whatever the strength of the “American West” theme in the center, that West is difficult to find in the fast-growing and quickly built suburbs to the north.

Freeway interchanges aren’t ever offered as objects for photography. I parked in some lot and wandered to the edge of this interchange. It was golden hour, so an ideal time for photography, and considering the August heat all that grass was remarkably green. This interchange serves as a kind of palate cleanser. North of here a different set of themes would proliferate as we left the West behind.

Turning from that freeway interchange I was facing warehouses. From a scraggly sidewalk I looked over a barely-there strip of landscaping to the parking lot and wall that carried a name I didn’t recognize. RPM Expedite turned out to be a logistics corporation, handling specialized transportation. For example, you need to ship large goods overseas to a trade show, RPM expedite will handle the connections and customs paperwork. Perhaps you need to transport oversized objects within the US, RPM Expedite will secure the right trucks and fill out the permits.

Some of the trucks might carry a logo or brand since they’ll be visible on the road, but the warehouses themselves are largely blank. We could be anywhere—nothing here indicates being “Where the West begins.” These warehouses deliver the stuff that allows corporations and households to assert their own private meanings. I feel these warehouses as a blankness at the heart of our contemporary life. They are the opposite of a civic black hole since they don’t suck matter permanently into themselves so much as ceaselessly send it all out.

Just beyond those warehouses is the North Fort Worth Baptist Church. All around the Dallas/Fort Worth metro I notice churches sitting just off major roads. I try to imagine the church leaders listing the pluses and minuses of this decision: 1) the church will be visible daily to thousands of drivers, 2) this will be inexpensive land, and...? And what else did they mention? The design of this church (built in 1985) was meant to grab the attention of drivers passing by, but what happens to the sense of the sacred or community when a church is cut off from neighborhoods and stands in space that otherwise would be occupied by a huge warehouse?

When my Mom was in her final terminal decline, I came to the contemporary service at North Fort Worth Baptist Church. This was July 3, so it was the 4th of July weekend, though I wasn’t in the mood for rah-rah patriotism. There were fewer people here than I’d expected. We sang with the worship band about how we were no longer “slaves to fear.” The pastor then talked through a passage from the Book of Philippians where Paul tasks believers with working out their own salvation in fear and trembling. The pastor likened salvation to a car that we’d been given, but which we needed to put effort into actually driving if we were ever to get anywhere. There were no windows in this worship space, and nothing in the message helped me grab onto the world outside.

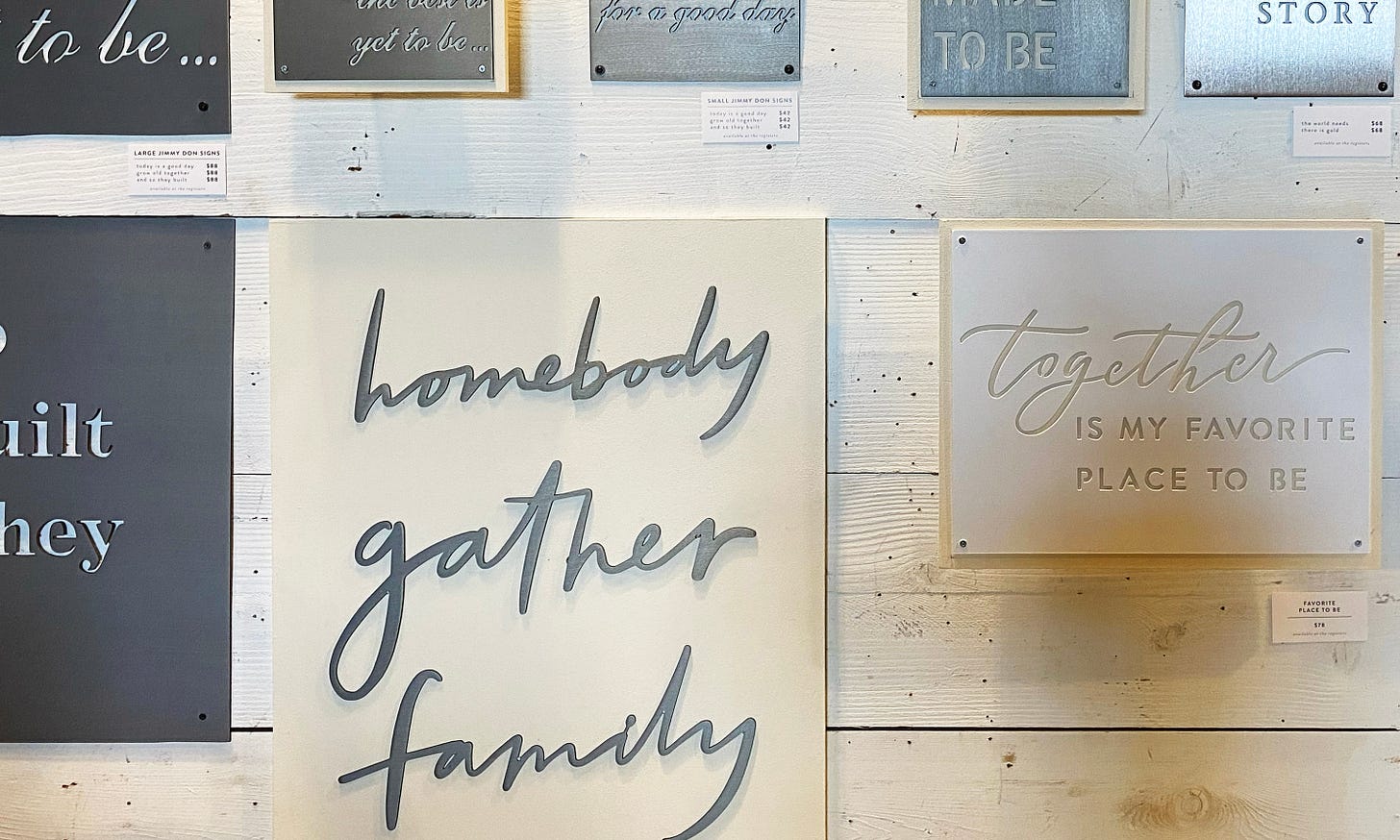

I slipped out of the worship space as soon as the service ended. I tried not to look conspicuous to the overweight and well-armed security guard standing in the hall. No doubt he was guarding against shooters. I reminded myself: don't act like you’re just here to case the place. Still I couldn’t help taking this photo of the fellowship space (again no windows!). The Evangelical allergy for images, or perhaps their extreme love for words, led to the framing of rather obvious words: “Gather” and “Fellowship.” On a central panel made of stained wood we were offered a “Welcome” not just to this room, but to the “family” that is this church. I kept moving.

That fellowship space made me think of another place my Mom and I had visited only the year before. We’d made the drive to Waco to visit Magnolia Market. It’s the home base for the Magnolia brand, run by Chip and Joanna Gaines. They began their careers as home flippers, buying low and renovating in order to sell for a profit. This practice itself was flipped into the reality television series Fixer Upper. That TV success was further flipped into a home decor empire, crowned by Magnolia magazine. Walking through this Waco space, I stopped to browse the word plaques for sale. These words and phrases elevated Home into a sacred space, and churches are keen to tap into that sacred feeling of Home through these same words.

Whatever the overlap of words, North Fort Worth Baptist Church lacked the charm of Magnolia Market. As I drove away after the service, heading to a service road that led to another road that led to the freeway onramp, I stopped to take this photo. In the distance was the straight line of another warehouse (will old warehouses ever become picturesque?). Across the road was a housing development trying hard to wall off this emptiness, whether warehouse, freeway, or church. In this space that resisted meaning the church blandly declared to passers-by: “Extending Hope Together.” What does it mean to extend hope? Does that mean “extend” in the sense of “holding it out” for someone, or in the sense of “making it longer.” The words had a carelessness and pointlessness that matched this space.

Driving north from the church and the warehouses drivers arrive at zones of strip malls and fast food restaurants, built up at every exit. The name for this particular retail development is “Presidio Towne Crossing,” which vies with “extending hope together” as a meaningless word triad. The sign goes on to list some of the businesses present here. These businesses all aspire to a national presence, so while downtown Fort Worth aims to construct a regional identity, that goal disappears as we start looking around these suburban new spaces.

This nearby box store for furniture and interior design didn’t seem to have sufficient cars to justify its 150k square foot showroom. I assume the customers would show up, some drawn by the advertised opportunity to buy items from Magnolia Collections, the interior design line from Joanna Gaines. It would be forgivable to mistake this for a church since many churches now resemble just another box store. The name “Living Spaces” refer to the room in private homes that Americans call “living rooms,” but the name also sounds like a close variant for a popular church name—Life Church. It’s not even inconceivable that some lost soul has shown up here on a Sunday morning.

Two premier fast food restaurants sit next to each other at Presidio Towne Crossing. They started their journey here from opposite sides of the country: Chick-fil-A in the Atlanta metro area, In-N-Out Burger in the LA area, its first drive-thru dating to 1948. Both aggressively expanded from their regional base and now trade on regional identity, using it to build and keep customer loyalty. Those palm trees in front of the In-N-Out call to mind California, especially since this Texas climate doesn’t naturally support palm trees. As is customary at In-N-Out restaurants, two palm trees are crossed into an “X,” an idea pulled from an old movie where such palm trees mark a buried treasure.

Chick-fil-A, you might notice in the last photo, has no palm trees out front, but it does have a flagpole with an American flag. At newer locations (like this one) the company devotes a huge portion of the lot to a two lane drive-thru. On busy days young workers stand under those red umbrellas and take orders from drivers. But there’s another way in which this drive-thru carries meaning. It’s an empty drive-thru in the middle of the day, as empty as the tomb of Jesus Christ on the first Easter morning! Since its founding Chick-fil-A has been closed on Sundays so that workers could go to church or spend time with family. This Sunday the drive-thru was again empty, and many others like me would briefly consider the corporate faith commitment leading to this sacrifice of profit.

I was caring for a parent in hospice, but I still needed to eat, and likely as not it would be fast food. I’d gone to the service at North Fort Worth Baptist Church thinking maybe I’d find comfort or insight in an Evangelical worship experience of the sort I’d grown up with. Now I was at In-N-Out, again seeking some comfort, but now with a quintessential comfort food.

Whenever I visited my Mom in Fort Worth we’d come here once for a burger. As a California native, now residing in Wisconsin, I relished a chance to revisit In-N-Out. Now as my Mom lay dying I returned again, on my own. I made my order this Sunday afternoon and waited for my number to get called. In-N-Out had made its name with burgers and fries, and they had hesitated to follow other fast-food brands into an expansive menu. Here it was still burger, fries, soft drink. Perfect.

The display box on the wall held In-N-Out swag such as this t-shirt. That mix of classic car culture and tall Mexican fan palms represented one imagined version of California. That sunset for me was pure 1991, a year of spectacular California sunsets after Mt. Pinatubo erupted in the Philippines. My parents had retired to Fort Worth, but they were by no means the lone geniuses who discovered they could sell a house in California and buy a bigger one in Texas, and be left with money to spare. The success of In-N-Out in Texas isn’t just a matter of burger quality, but a direct appeal to the place-nostalgia thousands of former Californians carry within themselves. These north Fort Worth suburbs offered a blank slate of meaning, and successful businesses delivered their own symbol systems to help fill that emptiness.

I ate my cheeseburger lunch and raised my Dr Pepper to see if a Bible verse was still printed there. It was: John 3:16. It’s the best known verse for American Evangelicals, “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life.” That’s how it exists in my mind, stilted language and all. And it’s not just the bottom of the cup, but on back of the fries tray is another verse (Proverbs 24:16) and on the hamburger wrapper still another verse (Nahum 1:7). As blank as an American fast food restaurant appears to be, and as much as I just wanted a burger, I was double wrapped at In-N-Out in the myth of California and Gospel promises of eternal life.

As I flew home I had a chance to reflect. The cloud formations gave an upward boost to my thinking. In these suburbs I was now leaving the tools of building meaningful places had given way to vast tracts of emptiness. I had come upon occasional turns to romantic versions of national or regional identity, but more common was the default use of Evangelical words and codes. I thought about my Mom living here through her last years, now dying in these barrens, and I could see no comfort, even as the largest questions about perishing and everlasting life became inescapable.